Interview | Plastic soup: a dish better not served at all

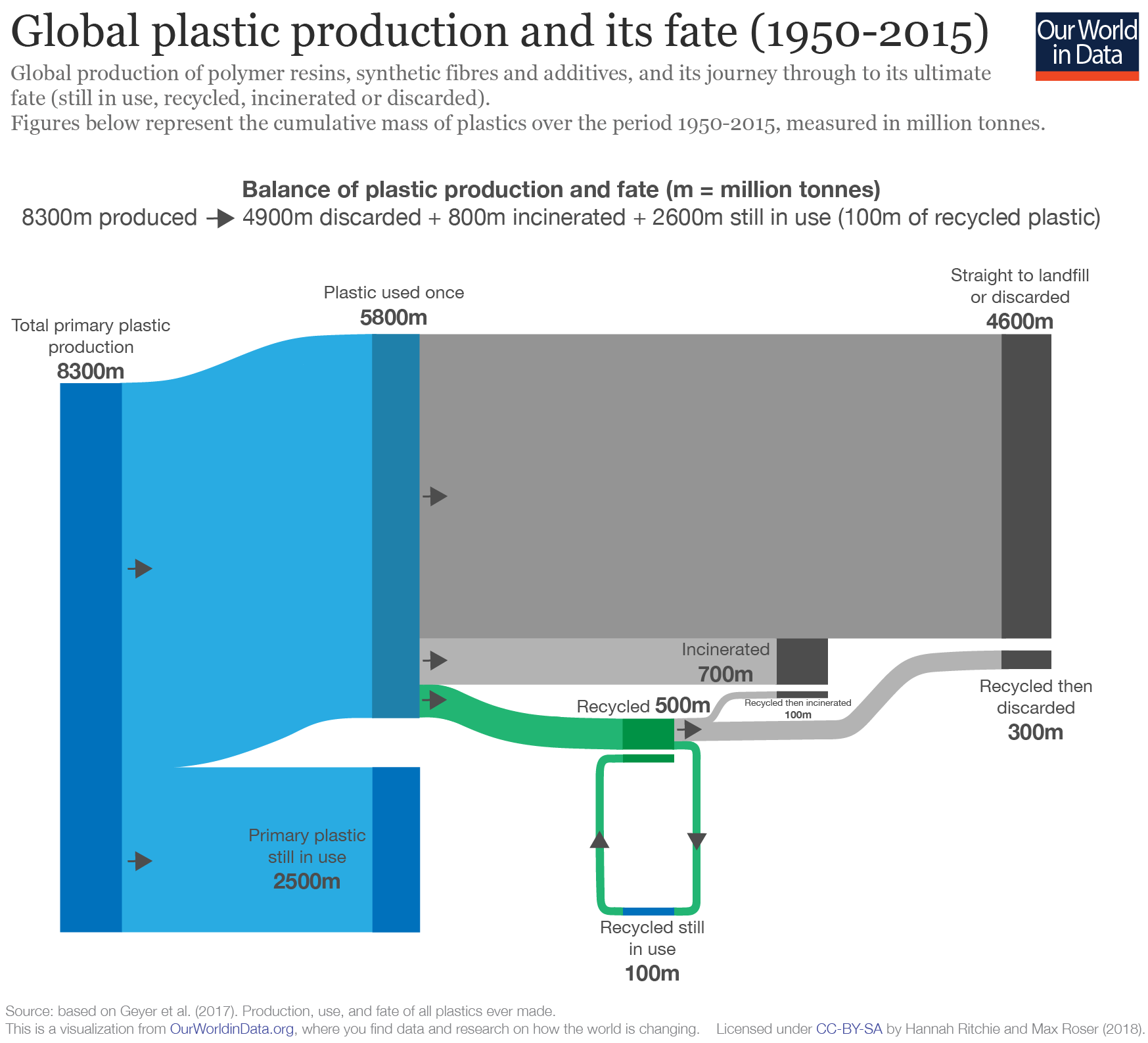

90.5% of plastic waste has never been recycled, as the Royal Statistical Society announced in January 2019. Some is incinerated, but 79% accumulates in landfills or in the environment. Plastic in the ocean – plastic soup – causes damage to animals, ecosystems, and possibly also to humans. With the production of plastics still growing, this problem will become even bigger. PRé’s Daniël Kan interviewed Peter Kershaw, an independent research scientist specialised in marine plastic pollution.

About Peter Kershaw

Peter Kershaw is an independent consultant in the field of marine environmental protection, based in the UK. He splits his time between consultancy and working within the United Nations and related bodies, largely on a pro bono basis. This follows a career of over 30 years as a research scientist at a UK government research institute, located in Lowestoft on the North Sea coast. He started to develop a particular interest in the issue of marine plastic litter and microplastics in 2008, and since has taken part in a number of international and multidisciplinary assessments of the sources, fate and effects of plastics, and associated contaminants, in the ocean, published in 2015, 2016 and 2017. He is the author of several reports on the topic for United Nations agencies, including a 2015 study on ‘biodegradable’ plastics, the 2016 report on marine plastics for the 2nd UN Environment Assembly and, most recently, a study exploring alternatives to conventional single-use plastics. These studies on marine litter have helped to convince him of the need to consider all aspects of the production, use and post-use/end-of-life stages in the life cycle analysis of the plastics economy, and the need to apply a similar approach when considering possible alternatives to conventional polymers. Currently, he has a 3-year, part-time position supporting the EC DGENV in its Environmental Diplomacy with regard to the circular economy, resource efficiency and marine litter, in the context of the G7 and G20 process. He is Chair of GESAMP, a UN advisory body that covers a wide range of marine environmental issues.

How did you get involved in studying plastic soup?

I raised the issue within GESAMP about ten years ago, because I thought it deserved more attention. Since then, GESAMP has been spending more time on the sources, fate and effects of microplastics in the marine environment. Lately, our focus has extended to all sizes of plastics.

I became involved in life cycle assessment (LCA) through my work for the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). LCA is often used to justify the production and use of plastics in preference to other, natural, materials on the basis of emissions and resource use. But end of life, when plastics become a nuisance, is often missing. This bothered me, as an outsider.

Do you feel the LCA community is missing part of the impact of plastics?

Yes, they do not consider the plastic soup part of the equation – plastic pollution in the ocean after end of life. Studies argue that the benefits of plastics far outweigh any disadvantages. But through incorrect assumptions or incomplete models, you can make an LCA favour one alternative over another.

Why is it interesting to study sources, fate and effects of microplastics in the marine environment?

Microplastics research has exploded in the past ten years and recently in the media. When the problem of microplastics first emerged in the scientific community in the 60s, it was largely ignored. The focus – and the money – went to more classic pollutants like radioactivity, nutrients, contaminants, heavy metals such as lead, and later organic pollutants like PCBs (polychlorinated biphenyls).

But the amount of plastic in the ocean just kept on rising, and the idea of plastic soup is now widely known. I am not sure why microplastics recently triggered the imagination. One of the issues is that plastics act a bit like oily fish. Oily fish have the problem that they attract contaminants and end up containing a higher proportion of organic contaminants. Plastics act a bit like oils, so if you have lots of plastics and contaminants in the ocean (humans seem to be good at contaminating the oceans), that might be a route for these contaminants to get into our food chain.

What are the major sources of marine plastic pollution?

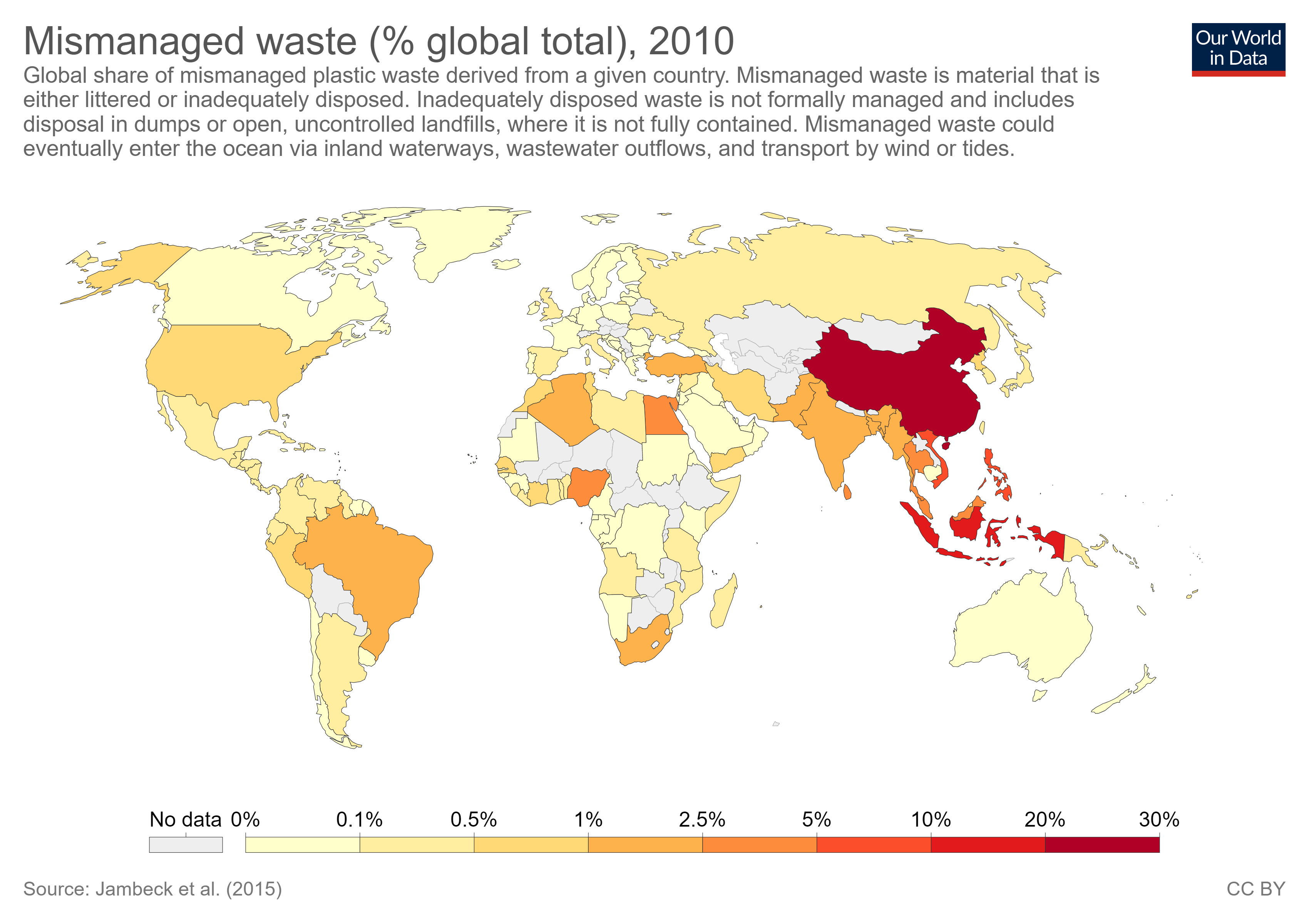

It is often said that 80% of sea waste comes from land, but there is actually very little evidence to back this up. We have to look at it regionally. However, we can make some general remarks.

The most important source of pollution is mismanaged solid waste. Here, we can just put stuff in the bin and it is dealt with, but this is not the case in large areas in the world. Another driver is shoreline tourism. The third big source is fisheries.

Plastic pollution can have direct and indirect impacts on economic activities. Most obvious risks come from larger items such as ropes and fishing gear. Boat propellers can get stuck, bags might block cooling water intakes, and so on. There are also aesthetic impacts. In tourist areas, municipalities spend a lot of money on cleaning beaches because tourists do not like dirty beaches. The potential impacts of microplastics are less easy to explain and we currently have very little scientific evidence that they actually cause effects. The damages are still only potentially there.

What is the fate of plastics in the ocean?

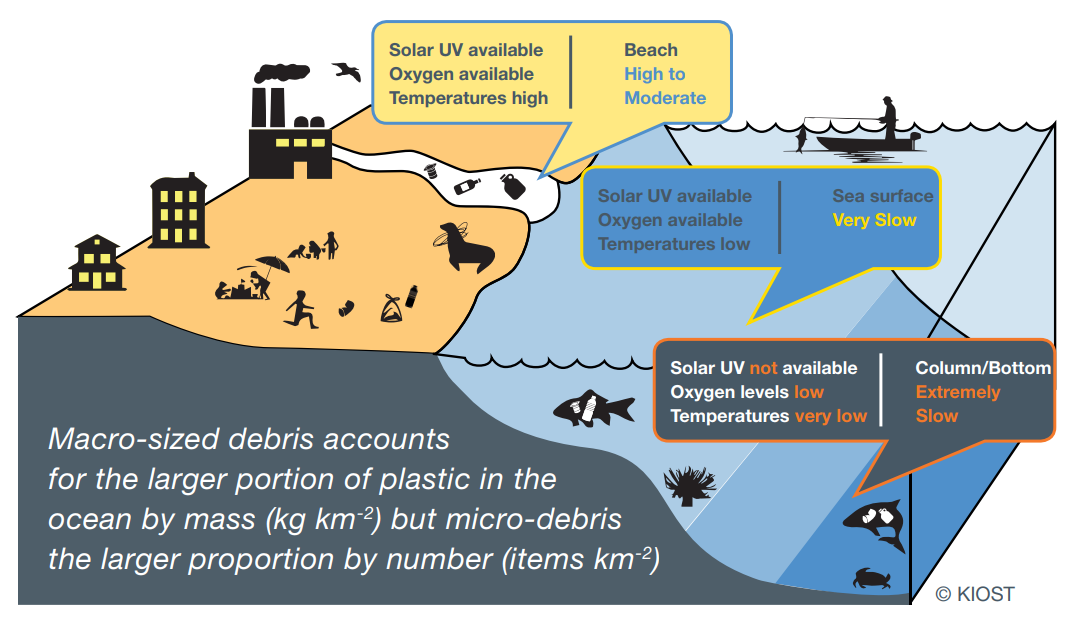

Degradation happens fastest due to UV radiation, for instance on a sunny sandy beach. Once the plastics reach the ocean, especially when they reach parts of the ocean where light does not easily reach, they degrade much slower. Plastic bottles on the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea will probably stay there for a long time.

“The production of microplastics by the fragmentation of larger plastic items is most effective on beaches, with high UV irradiation and physical abrasion by waves. Once submerged, cooler temperatures and reduced UV means fragmentation becomes extremely slow.”

Source: GESAMP, © KIOST.

Can we solve this problem without drastically reducing the amount of plastics we use?

Better waste collection management is needed urgently in many parts of the world but will not help in the long run. If you keep the same linear production > use > disposal model, you are just going to keep producing more and more waste. But waste can be valuable, we should not be putting it in a landfill. We have to start redesigning for recycling more. It is important to make materials less hazardous, so waste streams can be used safely for things like children’s toys. It is an incredibly complicated issue.

What are the ecological impacts of microplastics in the marine environment?

The impact of larger items in the plastic soup can easily be seen: more environmental stressors might push threatened species over the edge. The Hawaiian Monk Seal, for example. Turtles that cannot distinguish between jellyfish and plastic bags. A particular albatross which tries to feed anything floating in the water to its chicks. It is fairly straightforward to find the evidence for these impacts on specific animals. A more general problem is abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear and lost crab pots.

When it comes to microplastics, the jury is still out. There is an effect when fish and other organisms are exposed to unrealistic concentrations of microplastics in the laboratory. Trying to work out what happens in reality is very difficult, because we do not know if there is a threshold or a linear response to different concentrations of plastics.

What are the impacts on human population?

When it comes to human impacts, there is even more uncertainty. The Food and Agriculture Organisation concluded that the impact on human health from microplastics is minimal. That may be because we do not know very much. But impacts may already be occurring: worried consumers who stop buying fish, for instance. This is a potential economic impact on the fishers and health impact on the consumers if they stop eating fish protein. Research that concludes something is safe may still not persuade people.

How can LCA contribute to solving marine plastic pollution?

I see value in life cycle thinking and procedures, but the current procedures are not ideal for taking plastic soup into account. Some studies suggest that we have to use a cotton bag 100 times before the environmental burden outweighs the burdens of 100 single-use bags. But what if one of these plastic bags ends up being swallowed by a turtle and it is the last one he can take? This is only a hypothetical, but LCA needs to take this end of life scenario into account. We need a model or a framework and more data on the environmental damage from marine plastics.

Once we get a better view of the full picture, we can make informed decisions and compare positives. Plastics also have positive impacts, like preventing food waste. In developing countries, 30-40% of the food never makes it to the market. Today’s airplanes use far less fuel and are much quieter because half the plane is made out of plastic. We need to keep putting things into perspective.

I think we need to work together across disciplines. Sometimes I go to meetings where people have never heard of LCA, and sometimes I go to meetings with LCA people who never heard of the Basel Convention on waste management. We have to break down these barriers if we want to find out which environmental issues are most pressing and how to solve them.

Daniël Kan

Expert

Daniël worked at PRé from 2018 until 2023. As a Sustainability consultant, he collaborated on many LCA projects, especially in the fields of biodiversity and ecosystem services. He also provided SimaPro, LCA trainings and biodiversity footprinting trainings.